An Untold Story of Dairy Production

Text and images by Jo-Anne McArthur.

For the past fifteen years, my work as an animal photojournalist has taken me through the world of dairy production, far beyond the marketing campaigns, and taught me an entirely different story about milk.

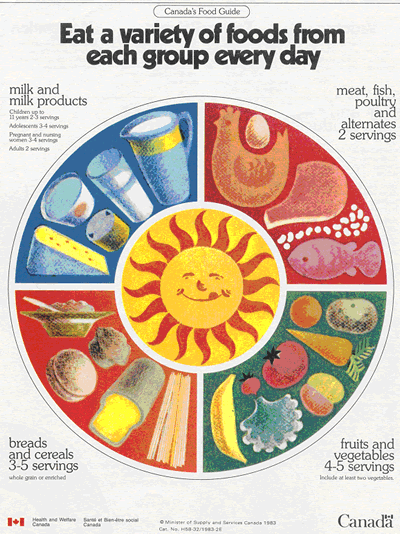

When I was a kid in the ‘80s, cow’s milk was ubiquitous in school life. Parents paid a token amount so that their child could have a personalized carton of milk every day at lunch. We needed cow’s milk so that our bones would have a fighting chance at growing strong, and preventing later-life diseases such as osteoporosis. Since 1942, Canada’s Food Guide promoted milk and dairy products as a standalone food group that we should consume, ‘as available.’

The Globe and Mail – Canada’s Food Guide Through The Years

However, in early 2019 sweeping changes to the Canada Food Guide provided an evolved understanding of our nutrition needs; gone are the pictures of milk and dairy products floating across the food guide rainbow, and they are no longer included in the long list of healthy options for school snacks. Milk and milk products are now lumped into the ‘protein’ food group and surrounded by disclaimers: “Among protein foods, consume plant-based more often”, and “Make water your drink of choice.”

Today, Dairy is still the largest sector of agriculture in Ontario, where I live, and according to the Dairy Farmers of Ontario, the elementary school milk program serves 70% of Ontario schools.

Slick marketing campaigns still target in-school education programs that tell parents and kids that cows are happy, and their milk is a necessary building block for any child’s development.

For the past fifteen years, my work as an animal photojournalist has taken me through the world of dairy production, far beyond the marketing campaigns, and taught me an entirely different story about milk.

A dairy farm. Taiwan, 2019.

In my twenties I took a deep dive into understanding animal use and food production, but even then, dairy was not on my radar. I understood dairy to be healthy all around; that no one was hurt in the making of it and certainly no one died. I had absorbed pictures of dairy cows living in pastures from the side of milk cartons and on TV, and had fond memories of meeting cows on a visit to The Central Experimental Farm in Ottawa. I was an animal lover from a young age, and my family is particularly fond of this photo of me, aged three, admiring the Jersey cows.

I had been a vegetarian for a few years before I decided to do a one-month internship at Farm Sanctuary in Watkins Glen, New York. The Farm was the first of its kind: a sanctuary for animals who had been rescued from all areas of factory farming.

Interns at Farm Sanctuary are asked to participate in a vegan lifestyle out of respect for the animals. I felt that this was extreme, but I’d do it, and resume vegetarianism upon my return to Toronto.

My start date was April 1st, 2003. April Fools! The joke was on me. That was the first day in my life as a vegan.

It was there where I learned that animals do get killed in the dairy industry. Cows are killed when their bodies are broken down, or “spent”, from the constant cycle of pregnancies, and then typically slaughtered for cheap hamburger before the age of six. I learned that a healthy cow can live twenty and even thirty years, but that their health, and therefore milk productivity, declines with each pregnancy until they are replaced by younger cows. Cows are also incredible mothers. When given the chance to stay together, they share an unbreakable bond for life.

And about that pregnancy. I believed that dairy cows just produced milk. I didn’t consider the baby involved.

Cows are artificially inseminated and carry a calf for nine and a half months before giving birth. The baby is taken away at birth so that humans can consume the breast milk. We are the only species that consumes the milk of another species, and continue to drink milk into adulthood.

Cows aren’t the only ones dying in milk production. Pregnancies create a whole other animal industry: veal production.

I felt embarrassed when I came to understand that dairy production and veal farming were inextricably linked. I wondered how I could not have just thought about it and realized on my own? I’m just glad that I eventually did. To consume veal was to support the dairy industry, and vice versa. Some females born to dairy cows become veal as well, or become dairy cows also destined for multiple pregnancies and short lives, denied the bonds and joys of motherhood. Oh dear. It was time for me to give up cheese, for good.

I could not believe that I did not know that this was the business of dairy-making.

Top: Still wet from birth, a calf is wheeled away from her mother to the veal crates at a dairy farm. Spain, 2010. Left: A dairy cow tethered by her neck in a barn. Taiwan, 2019. Right: A dairy cow. Taiwan, 2019.

Many people choosing a plant-based diet start by eliminating red meat, often followed by pork, lamb, and then chicken and fish. This had been my process as well. But what I was learning at the Farm was eloquently explained in Eric Marcus’ book “Meat Market: Animals, Ethics, and Money”: that from a harm reduction perspective, dairy should be the first in the elimination process.

Over the course of my work as an animal photojournalist, I have visited dairy farms on five continents. I’ve toured organic, family run farms, as well as huge, industrial spaces. I have photographed involuntary inseminations, births, confinement and tethering, the daily lives of veal calves and dairy cows, as well as their transportation and slaughter.

Here are their stories:

Jump to: Spain, Canada, Australia, Israel, Taiwan, USA

Spain, 2010

The investigative team at Animals Equality and I were invited to document a day in the life at an organic, family-run dairy farm. We filmed artificial insemination, birth, a newborn calf being taken away from her mother, the veal crates, and the milking barn.

Canada, 2014

It was brutally cold on this January day in Canada, 2014. As we drove through white-outs in a farming belt in Quebec, we stopped to photograph the rows upon rows of calves in crates. They were nervous but curious, and separated from their mothers in a barn next to the crates.

Australia, 2017

One of the largest dairies I’ve ever visited was in South Australia. Cows were kept in open-air barns (not at pasture). As with many small and large dairies, the animals stood ankle-deep in their feces. Though veal crates are illegal in Australia, the farmers did show us an area where calves were kept communally – with crates – apart from the cows.

Israel, 2018

Dairies are a common agricultural practice on kibbutzim in Israel. This kibbutz near Haifa was home to thousands of dairy cows and calves living in unkempt barns. As in many countries, calves are separated from their mothers, and we witnessed the use of spiked nose plates on older calves, which aggravate the cow’s udders when they try to suckle.

Taiwan, 2019

In 2019, the We Animals Media team visited dairy farms with the Environment and Animals Society of Taiwan (EAST). Specifically, we were looking to document the practice of tethering, which largely immobilized cows by their necks, and limits their movements by strapping their hind ankles together. Additionally, we witnessed many animals living ankle-deep filth in tiny enclosures, and calves separated from mothers.

USA, 2022

In February 2022, Jo-Anne McArthur joined Jason Bolalek, Founder of Destination Liberation in Vermont, USA, to document a calf rescue and the reason why so many calves are being shot. The state of Vermont is known for its dairy farming and milk production. Each year, more small farms close, and larger farms increase their capacity to hold cows and produce more milk. See and read more from this investigation.